|

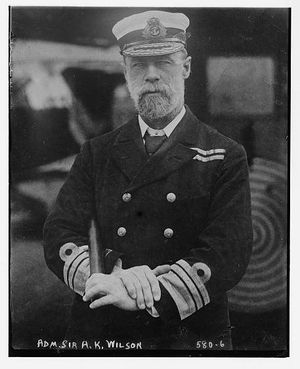

| Adm of the Fleet Sir Arthur K Wilson, VC, GCB, OM, GCVO |

Arthur Knyvet Wilson was born in Swaffham, Norfolk, on 4 March 1842. He was the son of Rear-Adm George Knyvet Wilson and nephew of Maj-Gen Sir Archdale Wilson, who commanded the garrison during the Siege of Delhi (Arthur was to inherit the baronetcy awarded to Sir Archdale for this).He was educated at Eton and entered the Royal Navy in 1855.

Early Career

As a Midshipman, he served on HMS Algiers during the Crimean War. The ship served in the Black Sea, near Sebastapol and was involved in the bombardment of the Kinburn forts. Wilson transferred to HMS Colossus when the Algiers went for a refit in Malta. While serving on this ship, he was sent ashore to search for an Army Captain’s dog that had got lost near Balaclava. By the time he returned, the ship had sailed for Britain and he was forced to use another ship to return home. He was then posted to HMS Raleigh which was to serve on the China station. In March 1857, the ship ran aground on a submerged rock and was lost. The officers and men were landed and Wilson was then transferred to HMS Calcutta, the flagship. He was serving on this ship during the Second China War.

In 1867, he was one of the party of

British naval officers sent to Japan to set up a school for naval

officers at Yedo and take up the post of Instructor. In 1870, while at HMS Excellent, he was a member of the committee

appointed to inquire into the capacity of the Whitehead Torpedo. In 1876, he became Commander at HMS Vernon, the newly established

Torpedo School at Portsmouth in recognition of his previous experience

in torpedo research. While he was there, he was promoted to Captain

in April 1880 and asked to re-write the navy’s torpedo manuals.

He also invented aiming apparatus for the torpedo and worked out

a method of submarine mining and countermining adapted to naval

requirements. In 1882, Wilson was appointed to command HMS Hecla,

a torpedo depot ship.

Egypt and the Victoria Cross

Hecla was used as a transport ship during the Anglo-Egyptian War. The ship contributed

a small detachment as a Naval Brigade for the second battle of El Teb on 29th February 1884. Although Wilson was

not actually part of the brigade, he joined the battle as an observer.

What happened next is recounted in the London Gazette for 21 May 1884.

Sailors using a ship-based Gardner Gun This Officer, on the staff of Rear-Admiral Sir William Hewett, at the battle of El-Teb, on the 29th February, attached himself during the advance to the right half battery, Naval Brigade, in the place of Lieutenant Royds, RN mortally wounded. As the troops closed on the enemy's Krupp battery the Arabs charged out on the corner of the square and on the detachment who were dragging the Gardner gun.

Captain Wilson then sprang to the front and engaged in single combat with some of the enemy, thus protecting his detachment till some men of the York and Lancaster Regiment came to his assistance with their bayonets.

But for the action of this Officer Sir Redvers Buller thinks that one or more of his detachment must have

been speared.

Captain Wilson was wounded but remained with the half battery during the day.

Richard Noyce, Curator of Artefacts at the National Maritime Museum, gives a more vivid account in this video:

Wilson was presented with the Victoria Cross at a special

ceremony on Southsea Common on 6 June 1882. He recorded in his diary 'Docked ship. Awarded Victoria Cross.'

Later Career

Later Career

In 1889, he was again appointed to command HMS Vernon. In

1893, he was appointed to HMS Sans Pareil and witnessed the collision of HMSs Camperdown and Victoria, which led to the sinking of the

Camperdown with severe loss of life, including Admiral Sir George

Tryon.

Wilson was promoted Rear Admiral in 1895. He was appointed as Controller of the Navy and Third Sea Lord. Four years later, in 1901, he was promoted again to Vice Admiral and made Commander in Chief of the Channel Squadron. During his period in this position, he improved and brought in modern methods of tactics in view of the technical advances in battleships.

Wilson was promoted Rear Admiral in 1895. He was appointed as Controller of the Navy and Third Sea Lord. Four years later, in 1901, he was promoted again to Vice Admiral and made Commander in Chief of the Channel Squadron. During his period in this position, he improved and brought in modern methods of tactics in view of the technical advances in battleships.

In 1907, he was made Admiral of the Fleet by a special Order in Council, after successfully commanding the Channel and Home fleets. In 1910, he was appointed First Sea Lord. He did not favour the use of submarines as a means of firing torpedoes, famously calling them 'a damned un-English weapon'. After two years, he was dismiissed ('like a butler') after differences of opinion in regard to administration and policy with the First Lord of the Admiralty (his Parliamentary counterpart), Winston Churchill. On his 70th birthday he was placed on the Retired List and was made a member of the Order of Merit.

However, on the outbreak of war in 1914 he returned to assist Lord Fisher, the new First Sea Lord, at Churchill's request. Fisher and Wilson clashed continuously until the former's resignation in 1915. Due to strong opposition from sea-going admirals and others, Wilson was not re-appointed First Sea Lord

let it not be A. K. Wilson who is a man of quite inferior calibre and who backed up Winston in his folly over the naval attack on the Dardanelles. AKW is all right knocking down Fuzzy Wuzzies with his fists, or getting a cable round a bollard, but the idea that he is a strategist of the first water has no foundation in fact and he is dumb at War Councils and institutions of that characterHe retired for a third time in 1918. When his brother died in 1919, he became the 3rd Baronet. Wilson died on 25 May 1921 at his home in Swaffham.

The Medals

Sir Arthur's medals are held by the Royal Navy Museum, Portsmouth.

Victoria Cross

Knight Grand Cross, Order of the Bath (GCB)

Order of Merit (OM)

Knight Grand Cross, Royal Victorian Order ( GCVO )

Crimea Medal (1854-56), 1 clasp: 'Sebastopol'

Second China War Medal (1857-60) 2 clasps: 'Canton 1857' - 'Taku Forts 1858'

Egypt Medal (1882-89) 3 clasps: 'Alexandra 11th July' - 'El-Teb' - 'Suakin 1884'

Queen Victoria Diamond Jubilee Medal (1897)

King Edward VII Coronation Medal (1902)

King George V Coronation Medal (1911)

Grand Officer, Legion of Honour (France)

Order of the Medjidieh (3rd Class) (Turkey)

Order of Naval Merit: Grand Cross (Spain)

Khedive's Star (1882)

Turkish Crimea Medal (1855-56)

Knight Grand Cross, Order of Dannebrog (Denmark)

Knight Grand Cross, Order of the Netherlands Lion (The Netherlands)